Welcome to Shuo Huang's page!

About me

I was born and raised in Hefei, Anhui Province, China. Although Hefei was not a large city, I witnessed its significant expansion and development until 2016. Then, I started my academic life in different cities. I am now a joint PhD student between Tsinghua Univ. and Leiden Univ.

Anhui Province is renowned for its tourist attractions. Among them, Xidi Town and Hongcun are famous historical villages. The province also boasts the majestic Yellow Mountain, Mount Langya, Mount Jiuhua, and many other scenic spots.

In my free time, I enjoy music, movies (especially horror films), and animations (primarily from Japan and the US). I am often a "daydreamer," leisurely strolling down streets without a specific destination, but I also enjoy planned travels with friends.

Check my CV for further details.

Publication

Check Google scholar or ADS to see my refereed and first-author paper list.

Research highlights

- The Solar system terrestrial planets started in resonance

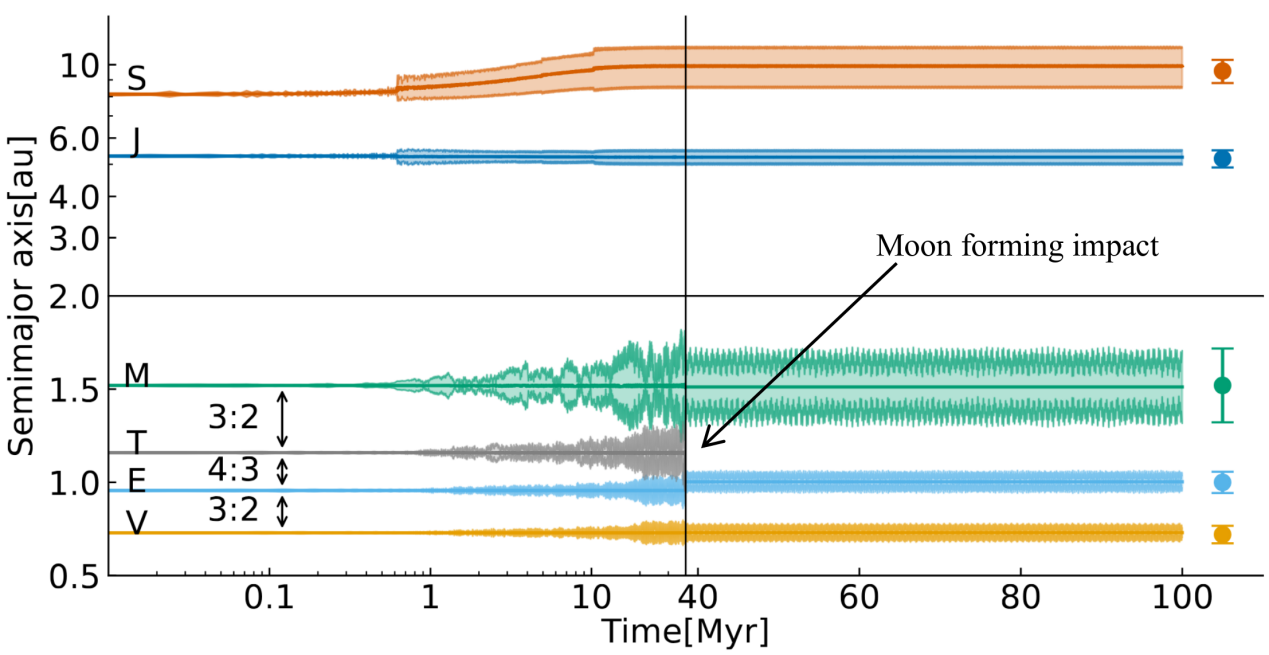

A research team involving scientists from Tsinghua University, Leiden University, and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ), recently investigated a scenario where the terrestrial planets in our Solar System formed early in its history. Their simulations suggest that the planets -- including the Moon-forming impactor Theia -- were once locked in a resonant chain during the lifetime of the Solar nebula. ...

However, Jupiter and the other gas giants destabilized the inner system (See figure 1 and 2), resulting in a collision between Theia and Earth between 10 to 100 Myr to form the current Earth-Moon system. The Moon forming impact appears to be quite common, in 20-50% of our simulations dependent on the initial architecture. The researchers found that the resulting planetary orbits closely match the current configuration, and the timing of the Moon-forming event aligns well with isotopic dating. Notably, the present-day 3.05 period ratio between Mars and Venus is an imprint of the broken resonance chain. Unlike traditional models that require many giant impacts and artificial damping to calm the planet orbits, this new scenario involves just one major collision -- the one that formed the Moon. As a result, the planet orbits emerge dynamically stable and less chaotic.

One prediction from the study is that Venus’s mantle may still preserve its original, primordial composition. Future sample-return missions to Venus could test the new scenario by analyzing isotopic signatures.Looking ahead, the team hopes to use this dynamical model to explain many exoplanet systems devoid of evolved inner resonance chain. Observations already suggest that young exoplanets often form in resonances, which may later break apart -- just like the inner Solar System did. If so, our Solar System may not be so special after all.

Show more

- On the origin of transition disk cavities: Pebble-accreting protoplanets vs Super-Jupiters

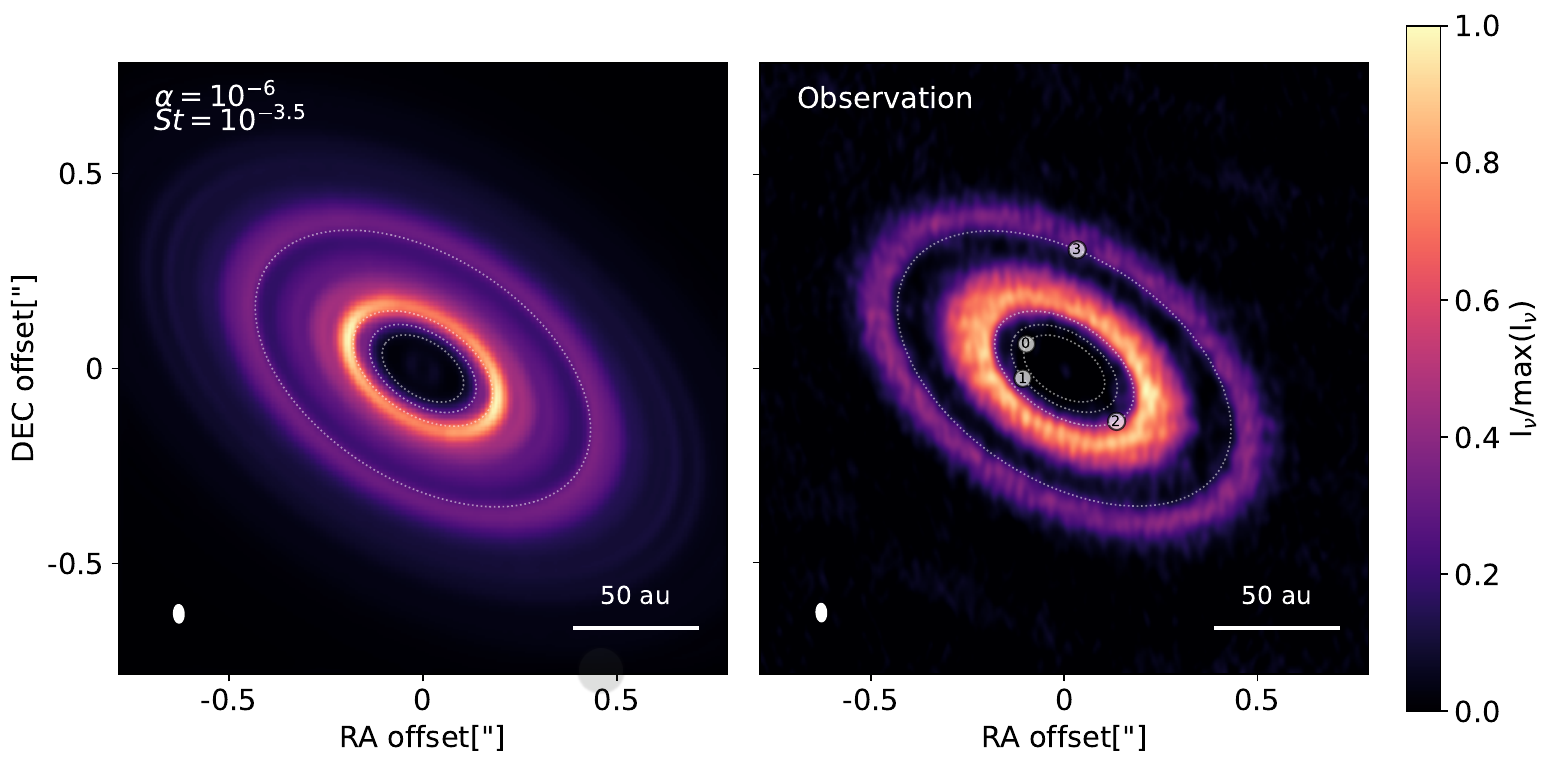

Recent advancements in astronomy have shed light on the mysterious processes occurring in protoplanetary disks—vast rings of gas and dust surrounding young stars where planets are born. Among these disks, some exhibit unique features known as transition disks, which display significant inner dust cavities. These cavities often indicate the presence of planets, yet the exact nature of these planets remains elusive. This study investigates how low-mass planets, specifically those that accrete pebbles, might create these cavities, challenging previous assumptions that such structures are solely the result of massive gas giants. ...

To explore this phenomenon, researchers employed numerical simulations that modeled the evolution of protoplanetary disks containing low-mass growing embryos. These simulations integrated 1D dust transport dynamics and pebble accretion processes. By varying the properties of both the planets and the disks, the team analyzed how these factors influence the resulting dust profiles. The findings reveal that multiple pebble-accreting planets can significantly reduce the dust surface density, thereby forming dust cavities consistent with observations of transition disks.

The study categorizes transition disks into two distinct groups based on their properties and the types of planets they may host. In Group A, massive gas giants create deep gaps in the gas disk, while in Group B, multiple smaller Neptunian-like planets contribute to the formation of inner dust cavities without creating substantial gas gaps. Notably, the characteristics of the dust rings formed in these disks—such as sharp inner edges—can provide critical insights into the underlying planet formation processes. The observational implications of these findings suggest that high-resolution imaging techniques, particularly with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), could further validate these models and enhance our understanding of planet formation in various disk environments.

Show more

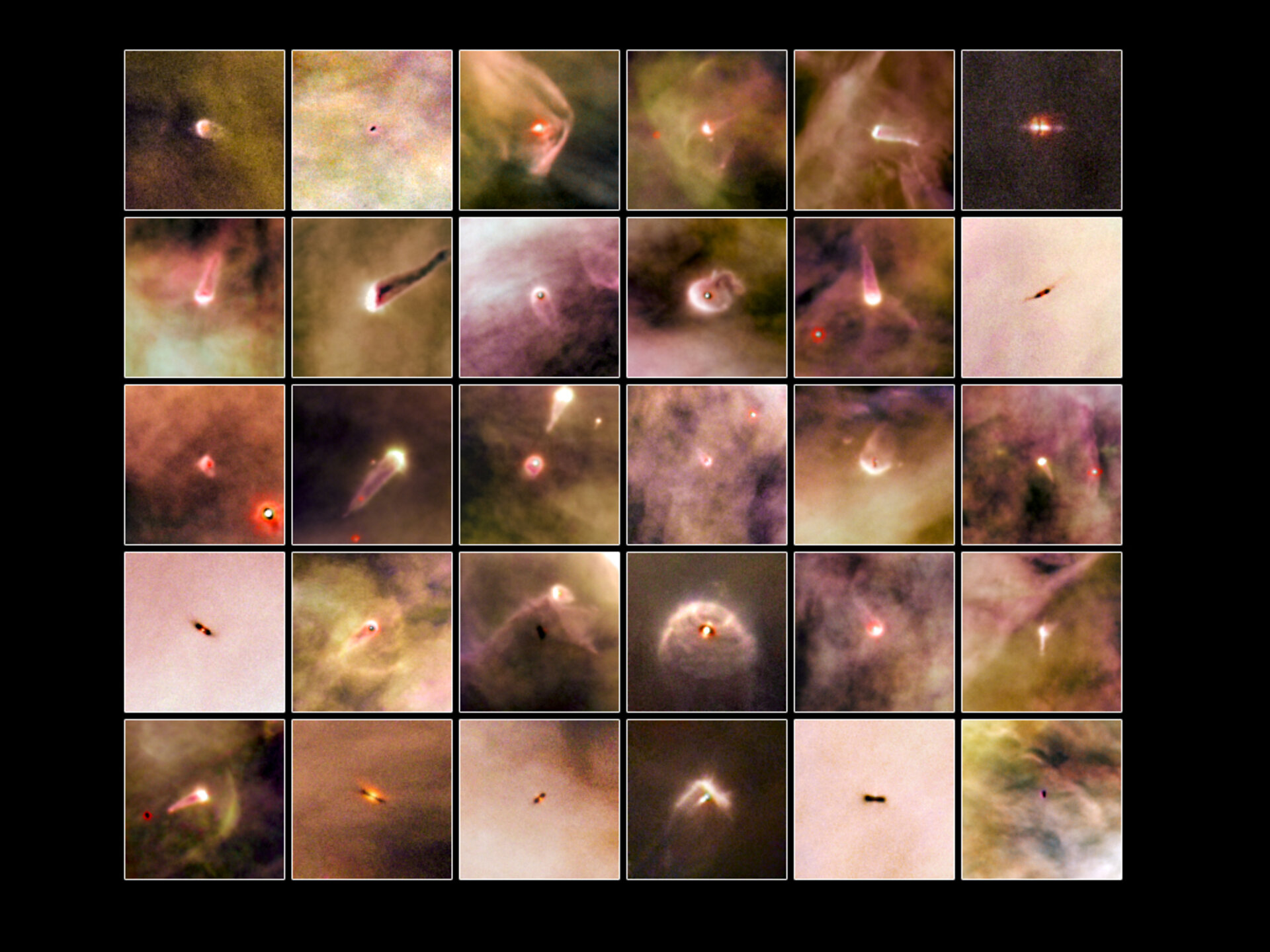

- Suppression of giant planet formation around low-mass stars in clustered environments

Observation already revealed that the birth environment of stars significantly impacts the planet-forming disks. The examples are the Proplyds in the Orion Nebula. The study introduces a novel planet population synthesis code that simulates planet formation in the proplyds in an Orion-like cluster, incorporating factors such as pebble accretion and the effects of nearby stellar radiation on protoplanetary disks. The researchers compared planetary systems formed in these clustered environments to those formed around isolated stars. Their simulations show that clustered environments hinder the formation of giant planets, like Jupiter, especially around low-mass stars. Instead, these environments tend to produce an abundance of cold Neptune-sized planets. ...

The team found that the intense radiation from nearby massive stars in clusters causes significant photo-evaporation of protoplanetary disks, stripping away the material needed to form large gas giants. This effect is particularly pronounced in disks around low-mass stars, which are less capable of retaining their gas in such harsh environments. The study also highlights how the presence of cold Neptunes and the absence of cold Jupiters in a planetary system could serve as indicators of the star's birth environment.

Future observations focusing on the prevalence of cold Neptunes and the scarcity of cold Jupiters around low-mass stars could provide valuable clues about the star formation history and the initial conditions in star clusters.

Show more

- When, where and how many planets end up in first-order resonances?

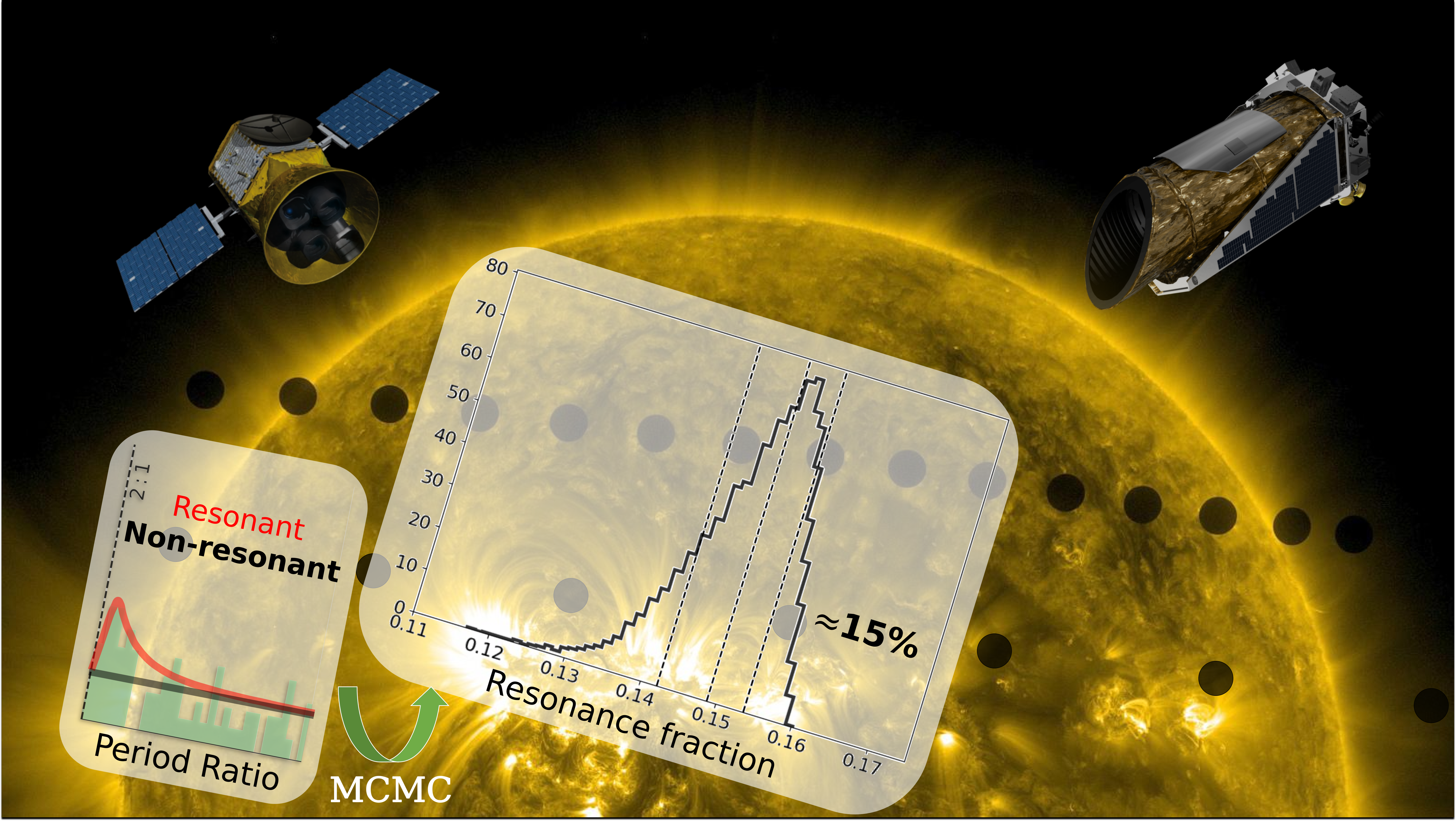

Over 5000 exoplanets have been discovered to date, with most of them being transiting planets detected by space missions such as Kepler, TESS, and ground-based observations. With such a large observed population, statistical analyses are possible. It is especially intriguing to do this for multi-planet systems harboring planets in orbital resonance. These systems provide indirect evidence of planet migration during their formation stages in gas-rich disks. ...

One prediction for a planet pair in a stable resonance is that the inner planet's orbital ellipse is misaligned with the outer one. Unfortunately, the transit method is usually not capable of observing the longitude of periapsis of the planet orbits, which makes direct identification of resonances impossible. Here, we have developed a statistical method to calculate the fraction of resonant planet pairs in the observed population, which does not rely on the exact orbital architectures.

This method uses two distributions of period ratios: a uniform distribution for non-resonant pairs and a log-normal distribution for resonant pairs. Applying a Monte Carlo Markov Chain technique, it is found that approximately 15% of planet pairs are in resonance, and the majority of resonant planets migrated over significant distances in their proto-disks. Furthermore, an upper limit on the surface density of the gas was derived, because two-planet resonance would break when the surrounding gas disk would become too dense. By refining the two-planet resonance trapping criterion, the upper limit of the gas surface density was found to be consistent with that of the Minimum Mass solar nebula.

In the future, this method may also be applied to extract the tidal interaction with the host stars, planetesimal scattering, and stellar encounter history of the observed planet population. With an increasing number of exoplanet detections foreseen in the coming decades, these findings will bring us a step closer to understanding planet formation physics.

Show more

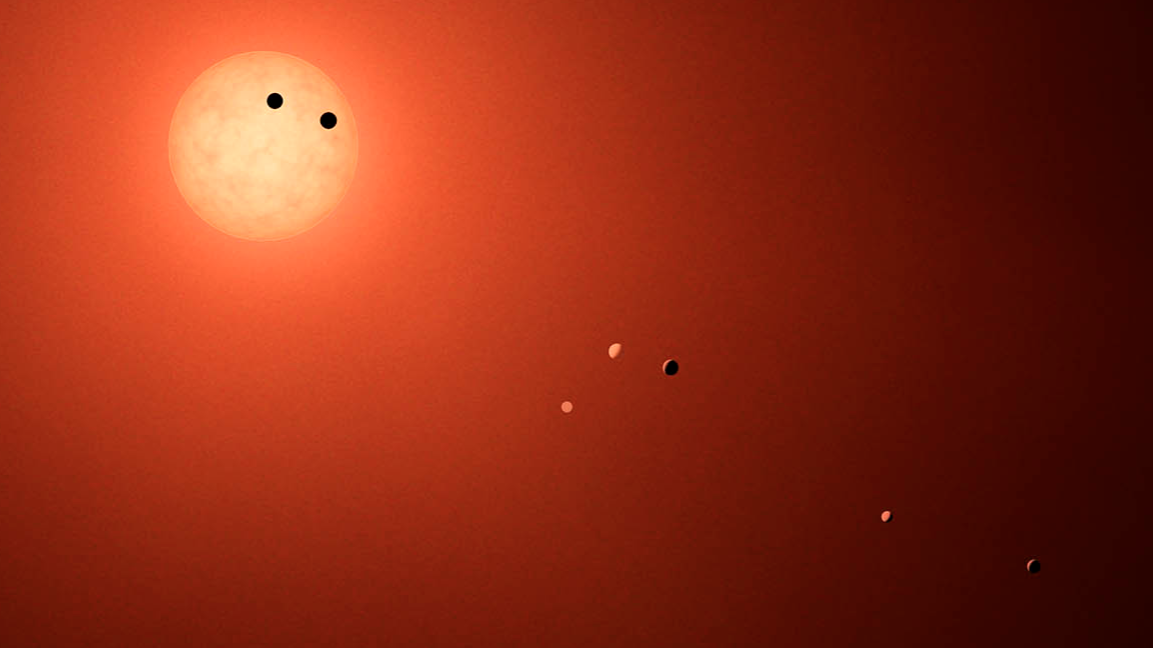

- The dynamics of the TRAPPIST-1 system in the context of its formation

The red dwarf star TRAPPIST-1 is home to the largest number (which is seven) of Earth-sized planets ever found in a single planet system. Three of these planets may be suitable to harbor liquid water or even life and will be prime targets for the recently-launched JWST spacecraft. Different from the terrestrial planets in our solar system, scientists have determined that it is likely that the TRAPPIST-1 planets formed early in their gas-rich protoplanet disk. Planets will then migrate inwards because of planet-disk gravitational interaction until they reach the inner edge of the gaseous disk. ...

But why do planets not crash into each other? Mean motion resonances can trap planets during their convergent migration at locations where the orbital periods follow a ratio of integer numbers. Examples in the solar system are the 1:2:4 resonance of Jupiter's moons Ganymede, Europa, and Io, and the 2:3 resonance between Pluto and Neptune. These are examples of first order resonances. However, in the TRAPPIST-1 system, the inner two planets are captured in weaker, higher order resonances than the outer planets. There must therefore be special mechanisms that operated in this system. Indeed, the peculiar dynamical configuration has puzzled many scientists since its discovery and attempts to solve it have typically focused only on a piece of the puzzle. In a recent study, accepted for publication in the MNRAS, Huang and Ormel have studied the problem from a planet formation perspective.

They propose a model in which planets form at the H2O snowline, then migrate towards the disk’s inner edge. The innermost two planets b and c enter a gas-free disk cavity early after their formation. Then, the outer planets migrate inward to join the resonance chain. Meanwhile, the spacing between planets b and c and the outer planets expand, because planet c still experiences a slight inward push from the disk. During its migration away from the disk edge, planet c can be trapped in three-body resonances at several locations, but this depends on the arrival time of the outer planets. When the outer planets arrive late, planet c will avoid the first locations and can then be trapped in the three body resonance corresponding to the location where it is presently observed. Hence, the dynamical configuration of the seven billion-year-old TRAPPIST-1 planets was already set in the first million years after their formation.

Show more

- An Active Flexure Compensation Method for LAMOST spectrograph based on BP-Neural Network

Researchers have developed an innovative technique to enhance the stability and accuracy of the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fiber Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST). This new method, based on a Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN), aims to counteract the effects of thermal-induced flexure, significantly improving the precision of spectrographic measurements. ...

The LAMOST telescope, a prominent Chinese national research facility, has been instrumental in surveying the Milky Way and extragalactic objects. However, the stability of its spectrograph has been a critical factor affecting the accuracy of its radial velocity measurements. To address this, the research team introduced an Active Flexure Compensation Method (AFCM) that utilizes deep learning models to predict and correct image shifts caused by thermal flexure. This method periodically adjusts the spectrograph camera system to align with reference images, ensuring more stable and accurate observations.

In their study, the researchers tested the AFCM on the LAMOST spectrograph and found it to be highly effective. The method reduced image shifts due to thermal flexure by a factor of four, achieving residual errors as small as a few hundredths of a pixel. The prediction model demonstrated excellent performance, with average compensation residuals well within the required stability range of less than 0.1 pixels every two hours. This improvement ensures that the spectrograph remains stable and accurate during long exposures, crucial for high-resolution spectroscopic surveys.

The success of this method marks a significant advancement in astronomical instrumentation, promising to enhance the quality of data collected by LAMOST. By leveraging deep learning techniques, this approach not only mitigates the impact of environmental factors on observational accuracy but also sets a precedent for future developments in the field. As a result, astronomers can look forward to more precise measurements, enabling deeper insights into the structure and dynamics of the universe.

Show more